The car crash that is the Australian royal commission into banking malpractice continues to cause headaches for the country’s banks. Criminal charges, class actions from exploited customers and further C-level banking resignations are all highly predictable; less easy to forecast is how the Australian banks will restore trust in the sector, reports Tom Ravlic

The royal commission into Australian banks and their exploitation of vulnerable customers has been tagged a “burning platform” by a beleaguered bank’s chief executive, and confidence in the whole Australian banking sector continues to haemorrhage in the light of evidence taken by the commission.

It has been almost nine months since the royal commission first began hearing the evidence from the banks, superannuation funds, regulators and the customers involved in Australia’s financial system.

The commission is being presided over by Kenneth Hayne, a former judge at Australia’s High Court. Evidence so far has unearthed multiple instances of poor financial advice, deliberate exploitation of customers known by banks to be vulnerable, and advisers selling products to clients for lucrative commissions and kickbacks.

Banks have also admitted to charging fees to dead people, and lying to regulators. The commission has also explored banks and their behaviour towards indigenous Australian communities, farmers and members of superannuation funds that are run by the retail banks. In the case of the latter, banks have been found to have charged fund members for services that were not provided.

Counsel assisting the enquiry is telling Commissioner Hayne that it is open for him to recommend criminal charges in a range of circumstances. Among the most egregious instances of malpractice are failures by National Australia Bank (NAB) and the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) to adhere to rules on superannuation.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataBank executives are issuing mea culpas by the truckload, but while admissions and promises to improve service have appeared, they are accompanied by enforcement actions that have resulted – or will result – in financial penalties and further actions.

CBA admissions

CBA CEO Matt Comyn admitted on 8 August 2018 that the bank had failed to serve its customers well.

“We just have to recognise we have not done a good-enough job for our customers. We got some things wrong; we have made mistakes. We absolutely need to make sure we do not make them again,” he said.

“A big part of my job, of course, is making sure we are a simpler and better bank for our customers, working closely with any customers who have not had a good experience, but most importantly making sure that those sorts of issues do not recur,” he added.

It is not just the pain the customers have experienced from the mistakes that needs to be avoided. CBA has been hit with financial penalties as well as additional compliance costs arising from the bank’s register of cardinal sins in customer service.

A settlement with Austrac cost the bank A$700m ($504m), the outcome of the bank’s failure to ensure that its systems properly tracked and reported suspected money laundering. CBA has also set aside A$1bn in additional capital on order of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) following the damning evidence.

Documents lodged with the Australian Securities Exchange also reveal that the bank has recognised additional provisions totalling A$389m in its 30 June 2018 financial statements.

“This comprises new risk and compliance provisions of $234m (a A$199m increase on the 2017 financial year) and one-off regulatory costs of A$155m,” the market disclosure states.

These amounts deal not just with the expenses related to the royal commission, they also incorporate expenses for the APRA inquiry into the bank, as well as class actions. Other CEOs have also acknowledged errors in their operations, with most of the admissions coinciding with the prodding and probing to which the royal commission and its team have subjected the banks.

NAB farmer apologies

NAB CEO Andrew Thorburn has, in a letter to the editor to one of Australia’s largest metropolitan newspapers, The Sydney Morning Herald, said that the royal commission is a “burning platform”, adding that it was forcing banks to make significant changes in the way they deal with customers, particularly those in the farming community who have been faced with the loss of their land because of unfair lending practices.

“NAB has been banking and backing farmers in Australia for over 100 years. We are the largest agribank in the country, with 550 passionate and dedicated agribankers, and we’ve done a very good job most of the time,” Thorburn wrote.

“But there have been some things, when you face into them and you look at them carefully – the royal commission being one of them – it’s clear you need to make changes.”

ANZ charges

There are also other long-term investigations that have begun to bear fruit for the regulatory bodies.

It is coincidental that the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions indicated in June 2018 that it would pursue criminal cartel charges against ANZ, its group treasurer Rick Moscati, two other companies and a number of other individuals.

“The charges will involve alleged cartel arrangements relating to trading in ANZ shares following an ANZ institutional share placement in August 2015,” ACCC chair Rod Sims said at the time.

“It will be alleged that ANZ and the individuals were knowingly concerned in some or all of the conduct.”

Pressure is also being applied by politicians in the Australian capital to have Hayne’s inquisition into the financial services sector extended even further to see what other problems and areas of banking malpractice the royal commissioner might find.

While extending the royal commission may provide those affected by banking malpractice with additional catharsis, one thing is certain: an extension is unlikely to help the banks focus on rebuilding customer confidence in their operations.

The challenge explained

The task of reputational repair should not be underestimated, Deloitte’s Willem Punt, a conduct partner who leads the firm’s trust management practice, tells RBI.

People are more likely to trust their own bank, Punt adds, but they are generally distrustful of banks as a class of entity – in the same way they might be sceptical or somewhat suspicious of power companies and telecommunication service providers.

Banks are already starting from behind in the reputation stakes when you take this into account, and the revelations from the royal commission have amplified and confirmed people’s general distrust.

Repairing relationships with consumers that have witnessed one story after another of poor behaviour from financial institutions towards customers emerge from the royal commission will be challenging.

Punt says trust will need to be rebuilt from the inside out, with reviews of internal controls and cultural issues within the banks and other financial institutions.

This will include reviewing – and possibly revamping – the way in which performance is assessed, and a re-examination of the way in which financial and other behavioural incentives are measured, to ensure that a business is not just making money through sales, but that the sales are being undertaken in an ethical manner.

“Banks recognise that, in the past, they really leveraged off scale of assets, but they now recognise that they need to leverage off scale of information and scale of trust,” says Punt.

“They are working very hard to regain and retain that trust. They need to do so in the midst of massive industry realignment. This is certainly not a simple challenge.”

Association response

Punt’s focus on fixing the internal processes of banks has already been acted on by a banking pressure group that is mindful of the need to ensure steps are taken to help rebuild confidence in financial institutions.

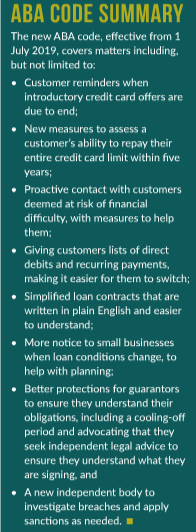

The industry association for financial institutions, the Australian Banking Association (ABA), released a refreshed Banking Code of Practice in the weeks leading up to the release of the Hayne royal commission’s interim report (see box).

The code has been revamped in an attempt to enhance customer protections. It applies only to banks at the present time, but the ABA has stated that the code should also apply to other entities that lend to customers, so there is no regulatory arbitrage taking place between a bank, credit union, building society or other form of lender.

The association has recommended industry-wide adoption of the code to the royal commission. ABA CEO Anna Bligh, a former premier of the state of Queensland, says the code should apply to any entity within which a customer has a lending relationship.

“Members of the Australian Banking Association have lifted the standard in banking with this new code, with customers the big winners,” Bligh says.

“Initiatives such as reminders when introductory credit card offers are ending, proactive contact with customers who might be at risk of financial difficulty, and simple, easy-to-understand contracts should be adopted across the entire industry.

“Particularly for small business, every lender – including building societies, credit unions and others – should give sufficient notice when loan conditions might change to help with future planning.”

Bligh adds that other lenders offer the same types of products as banks, but there is no uniform code that applies across the financial services sector.

The ABA wants a common industry code, approved by a regulator such as the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), to be part of the licensing process.

“While we fully expect further changes to be made to banking following the final report of the royal commission, it’s important that all lenders, such as credit unions, building societies and others, adopt the same rigorous standards to ensure there is consistency across the industry,” Bligh says.

Further measures

Self-regulation in the form of industry compliance with a code of practice is only one element of the regulatory puzzle that does not replace the function of the external regulator.

ASIC is responsible for regulating the consumer end of the financial services marketplace in Australia. The corporate watchdog, which has been criticised for failing to act on poor advisor and institutional behaviour, said in early August that it would be introducing on-site surveillance of banks in order to create an environment where more ethical and compliant behaviour is encouraged.

The announcement of the surveillance function follows damning evidence of the corporate regulator being lied to by financial services business AMP in lodgement documents relating to its compliance with Australian corporate law.

The royal commission has also exposed multiple instances of adviser conduct that were frequently not compliant with either institutions’ codes of conduct or financial services regulation.

ASIC chair James Shipton told a parliamentary committee hearing on 17 August 2018 that the in-house regulatory presence has the objective of forcing institutions to reflect on what a regulator will think about the decisions and actions of a business.

“If you, as a decision-maker inside a financial institution, are going to interact more regularly with a senior supervisory officer from ASIC, then that will bring regulatory issues – the physicality of the regulator, almost – front of mind,” the ASIC chair said.

“What we believe is important is that when decisions are being made inside a financial institution, they need to have a diverse range of different inputs. They need to be considering, ‘What would the regulator think about this decision? What is in the best interests of the consumer or the customer?’

“If you ask me, part of the failures of the financial system in recent years is that that type of thinking – that type of dissonance, that type of questioning – was not apparent in the decision-making rooms of financial institutions.”

Shipton underscored the focus on preventing breaches of law by having the so-called “cop on the beat” on the inside of Australia’s largest banks. This close continuous-monitoring program has between A$8m and A$9m allocated to it, and Shipton told the parliamentary committee that this “effectively translates to about 25 people”.

“We believe this is a very good start. We will test and monitor this and, if necessary, we will come back to you and your peers for support for expanding it if we think that it’s the appropriate thing to do. But, equally, when I say 25, it’s going to be virtual; it’s not just going to be those 25 professionals,” Shipton said.

“We will be using different resources from throughout ASIC. Importantly, we are also going to be working very closely with our peer agency, APRA, on this, who we have been keeping in close touch with, because of course they have a prudential supervisory role and responsibility.”

There is a problem for this regulatory David in dealing with the Goliaths of Australia’s finance sector. ASIC will be testing the effectiveness of this surveillance process, but the commission is already behind in the human resource stakes.

This makes it necessarily for the commission to use a riskbased method to determine what aspects of banking operations it should review at any point in time.

“We also have to realise that the average population of the Big Four is about 30,000 people,” Shipton explained to the committee.

“We at ASIC have 1,600, so there is a limitation as regards the sheer force of numbers.”

Spending any length of time within a bank could pose a threat to the judgement of staff from the regulator charged with keeping an eye on the banks and their practices. Shipton was previously a regulator in Hong Kong, and ran a similar programme there.

“I can personally speak from my own experience of running a supervisory team in Hong Kong, whereby teams would spend up to a number of months inside a financial institution,” he observed.

“But, again, the learnings of other jurisdictions – particularly the United States – are very important here. Firstly, it’s just training people before they go on site for the psychological risks of regulatory capture.”

ASIC also acknowledges that the scepticism of its investigators or reviewers should not be the first casualty of the war against banks’ poor compliance and inappropriate advisory practices